|

Call

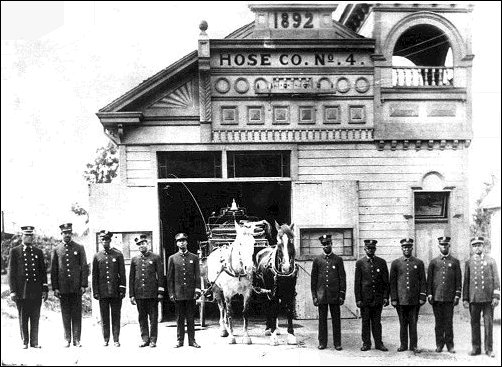

Fireman Sam Haskins is the earliest known black man to work on the Los

Angeles Fire Department. Born a slave in Virginia, Haskins came to

Los Angeles sometime in 1880. In 1892 Haskins worked as a "Call

Fireman", a paid position that was part time, filling in for members off

sick or on vacation. Most call firemen eventually filled a

permanent position when one became available. On November 19, 1895

an alarm came into Engine Company No. 2 located at 2127 East First Street.

The Engine Company responded, the hose wagon leading the way, the steam

engine following. Sam Haskins climbed on the rear tailboard of the

engine alongside of the engineer. Hitting rough pavement on North

Main Street, Haskins lost his balance and fell forward into the large

wheel on the left side of the boiler. He was fatally crushed and

died a short time later at the Engine House. Sam Haskins was a well

liked person around town and had many friends. He was the first

member of the department to die in the line of duty and his funeral was

attended by Chief Walter S. Moore, his assistant, Ed R. Smith and

Ira J. Francis, the electrician. A large detail of thirty men from

the fire department as well as members of the police department attended.

The cortege was headed by a band and Chief Moore delivered a grave side

address.

|

||||

|

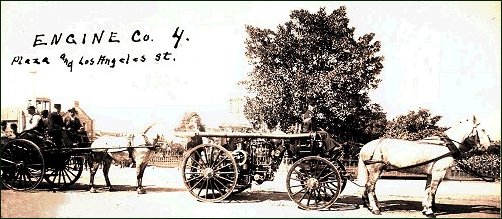

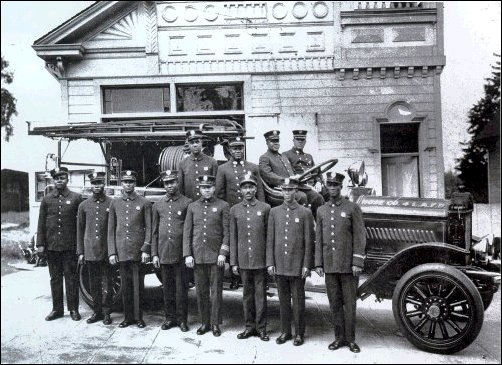

Lieutenant George W. Bright George W. Bright, hired October 2, 1897, was the first black member of the Los Angeles Fire Department. He was appointed by the Fire Commission as a callman and assigned to Engine Co. No. 6. Less than a month later on November 1, 1897 Bright was promoted to a full-time hoseman and assigned to Engine Co. No. 3. On January 31, 1900 He was promoted to Driver Third Class and assigned to Chemical Engine Co. No. 1.

On August 1, 1902 George Bright was promoted to Lieutenant. In those days chief officers made the promotions. However, before the commission would certify his promotion, Bright, being the first colored to express desires for such advancement was required to go to the Second Baptist Church and obtain an endorsement from his Minister and congregation.

Chemical

Co. No.1 / Hose Company No. 4

Chemical Company No. 1 |

||||

|

At the turn of the century the demographics of Los Angeles were changing. It was decided to move the black firemen from Hose Co. 4 and its all-white area and move them to Fire Station 30, an emerging mixed-race neighborhood. In 1924 Hose Co. 4 was closed and Engine Co. 58 opened in the same building. The black firemen were transferred to Engine Co. 30. |

||||

|

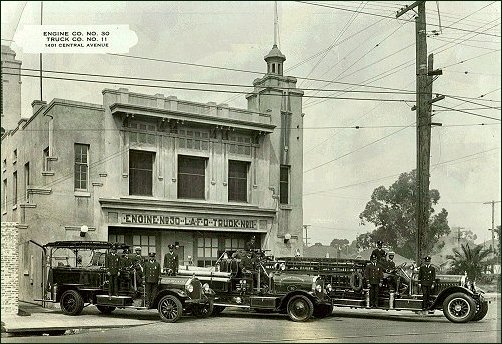

Acting Chief Engineer O'Donnell resented the City Council's interference of internal fire department affairs and refused- only he had the authority to assign personnel. In addition, Engine 30 required an engineer and the city's Engineering Department had a policy of refusing to certify blacks. Blacks were only trained to operate chemical hose companies. In the mid-20"s there was a sudden upsurge of men of color joining the fire service and a the need for a larger station intensified. The battle to make Engine 30 an all-black station took seven years. Engine 30 was a popular assignment and the white firemen threatened to strike. Racial tensions mounted. Never-the-less on April 16, 1924 the white firemen were removed and the black firemen from Hose 4 were transferred in.

The fire station housed Engine 30 and Truck 11 (In those years it was the practice to number the truck companies in sequence rather than taking the number of the station. Therefore Engine Company 30 housed the 11th truck company to come into city service. In 1932 this was changed and both companies reflected the fire station number. Engine 30, Truck 30, Fire Station 30, or simply "30's".) As more blacks joined the department Engine 30 became crowded. The firemen crowded the apparatus. The department's wrecker (heavy rescue) was assigned to Fire Station 30, simply because there was insufficient riding room for all the firemen on the engines and truck. Another station was needed. |

||||

|

Prior to 1940 This procedure violated civil service regulations, but was nevertheless followed to insure perpetuation of all-black staffing levels at Fire Station 14 and 30. Because the blacks were largely assigned to the two companies (five were in the fire prevention bureau and six assigned to supply and maintenance) the highest rank they could hope to achieve was captain. There were at that time only six black captains. White captains numbered 287. The department was satisfied with maintaining the status quo and could point to all-black companies in other large cities, notably New York, Chicago and Baltimore. The black firemen and their community leaders had mixed feelings. Many of the older black firefighters preferred the system as it stood. Some saw it as an advantage, as an easier chance for their individual advancement. Shift-trading was informal, but even more the blacks feared the probable hostility they could encounter if transferred to a white company. Another proposal was put forward by the black community and many black firefighters: convert Engine 21 and 22 to all-black companies which would open up promotional opportunities for more captains and enable the department to form a battalion of all black companies led by black chiefs on each platoon. A third approach was the one primarily espoused by the younger black firefighters who felt that the existing system was blocking them from promotions, even within their own stations. With all the positions in their own two companies already filled they had no place to go. They planned to make the LAFD their career and wanted immediate and total integration of the blacks at Fire Stations 14 and 30 into stations throughout the city. They found strong 14th Amendment Constitutional support for their ideas as well as the backing of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and Los Angeles' black-owned newspapers. |

||||

Slow integration was as much of an anathema to the blacks as was immediate, forced integration was to Alderson. The chief's position was that the city charter required him to make appointments, promotions and transfers "for the best interest of all the people of Los Angeles." He further pointed out that during his 13-year administration, no black had been passed over for promotion or denied appointment to the LAFD. Forced integration, said Alderson, would determinably impact the morale and efficiency of the department. Time and time again during the next three years, Alderson would say, "The chief engineer's responsibility is not to engage in any social experimentation." The black firefighters did not, of course, perceive of integration as a social experiment, but their constitutional right. As tempers flared on both sides of the issue, 90 percent of the department's white members began a campaign, including fund-raising, to support Alderson in the event the matter reached the courts. By 1954 there were 2500 whites and 74 blacks on the LAFD. Census figures showed blacks accounted for 10 percent of the city's population, but only 3 percent of the department's members.

July, 1953- Norris Paulson

Neither Bowron nor Poulson were friends of integration, Poulson had, in fact voted against fair employment practices legislation. Chief Alderson had remained officially neutral during the election but Poulson resented

his close ties to Bowron and sought a way to oust him. The integration issue provided

Poulson with a ploy to force Alderson's resignation. |

||||

"These circumstances constitute discrimination contrary to the constitution and laws of the state and nation, in that equal protection of the laws is being denied the Negro firemen," said the petition. Mayor Poulson's reply:

October 8, 1953 From that day forward, the integration issue escalated into a full-blown problem with

emotionalism overwhelming rational approaches to resolving the issue. Pressure put upon the Daily News publisher resulted in Ditzel being stripped of his

column. When firefighters discovered his byline missing from the paper, the department's

grapevine telephones passed the word among firefighters and their families. The Daily News

switchboard was so jammed by firefighters or their wives, friends and families canceling

subscriptions that reporters could not telephone their stories to the clerk desk. The call-in campaign boomeranged. The publisher charged Ditzel with instigating the

cancellations and put him off-duty for 10 days, prior to formal termination. The publisher

subsequently relented, but Ditzel was demoted to police reporter and later wrote the last

story ever to appear in the paper. The Daily News, for years in financial trouble,

declared bankruptcy and its assets were purchased by Poulson's foremost supporters, the

Chandler family-owned Los Angels Times and Mirror. Fire Commission orders Chief Alderson to submit a report in answer to the NAACP

petition.

|

||||

|

"I respectfully recommend that your board stand on Section 78 of the city charter

and that we continue to appoint, promote and transfer employees of the department for the

best interests of all the City of Los Angeles." -Alderson The fire commission approved Alderson's recommendation.

January 7, 1954 Four of the five commissioners and Alderson issued their own statement which said they had agreed to nothing of the kind. January

9, 1954 White supremacy groups throughout the United States deluge fire stations with black-hate mail, posters and pamphlets.

May 17, 1954 The historic decisions applied to school desegregation but their implications pertaining to the traditional operation of the LAFD rang loud and clear. The fire commission immediately asked the city attorney to rule whether the Supreme Court and other decisions applied to the LAFD. The answer was in the affirmative and Alderson was asked by the commission to respond on July 1, 1954. Alderson stubbornly reiterated his past position statements, while interjecting a new and headline-making statement: He would resign if the fire commission took over the assignment of personnel, transfers and other functions under his control. "I will not remain to see it (the LAFD) torn down to a second, third and fourth

rate department." |

||||

Without its own investigatory resources, the commission decided to wait-and-see the

committee's report while ordering Alderson to produce an integration plan. September

2, 1954

Alderson was told to produce a specific blueprint for integration by September 30. September 30, 1954 Mayor Poulson sets November 1, 1954 as a deadline for action.

October 14, 1954

|

||||

|

During the next four months, Alderson transferred four blacks to two all-white

stations. One of then almost immediately asked to be returned to his all-black station.

The gradual integration program ground to an impasse, but the battle was far from over and

would worsen before it was finally resolved. Beset by integration concerns, Alderson was growing physically and emotionally ill. The

firefighters still called him "Big John" - but not to his face. It was clear

that his was but a delaying action until full integration occurred with or without him as

chief engineer. November 1, 1955 The integration pressure cooker was, meanwhile, reaching the point of boilover. The battle spilled into the stations. Years of steadily-building tensions, frustrations, hate, rumors, propaganda and attacks upon Alderson by organizations and people who were perceived by the firefighters as knowing nothing about life in fire stations, provided all the necessary ingredients for turmoil. The inevitable consequences were further complicated by some white firefighters who did not support segregation. They said they would not hesitate to work with blacks and were among the first to be ostracized by longstanding firefighter friends on and off duty. Several of them who openly challenged segregation were severely disciplined for insubordination and other charges. As Alderson tested the mood of the firefighters by transferring blacks to all-white stations, he received little support from some chief officers and captains in the field, who frequently fueled the fires of hatred by their tacit encouragement of in-station opposition to integration. Their belief was that they were following the spirit of Alderson's policies and whatever means it took justified the ways. Apropos of the cliché: With friends like these, Alderson needed no more enemies.

The Hate Houses

In those pre-integration stations where blacks were assigned, kitchen privileges were often denied and a steady stream of practical jokes, a firehouse tradition, turned vicious, unspeakable, degrading and deplorable. When six blacks were transferred to Fire Station 10, the campaign of day-and-night hazings and harassments pushed matters to the point of imminent violence. |

||||

|

Other media as eagerly sought out stories which would illustrate racism in the LAFD. The department seemed all too eager to provide them. Two black firefighters and six white pro-integration firefighters were assigned to completely replace the all-white members of Fire Station 78 in the San Fernando Valley. Not one of the new assignees knew the district of commercial buildings, restaurants and high-value homes in the hills south of the station. Winding streets in the residential area were often difficult to find, even by the firefighters they replaced. The media was tipped. Headlines told of the dangers of Station 78's complement of officers and firefighters totally unfamiliar with hard-to-find locations in their first alarm district. The stories resulted in precisely the perception the tipsters' intended: Station 78 assignments were made to prove that immediate, forced integration was resulting in poor fire protection and hazards to residents in that area.

December 1954 December

15, 1955

The commissioners had flip-flopped so many times on integration, that nobody knew where all of them stood on any given day. Secondly, the commission would have sharply criticized Alderson if he had not acted, and one or more firefighters were injured or killed. And, finally, Alderson had already said he would retire on a date that was only two weeks away. By formally-charging the chief engineer with insubordination and going through the long process of firing him, the commission would only prolong and probably intensify the integration misery. The commission, realizing the shallow thought that went into their impetuous action, quietly let the dismissal matter drop.

|

||||

|

Alderson Retires Alderson retired on schedule and was replaced by Deputy Chief Frank Rothermel who said he not only fully-supported Alderson, serving as interim chief engineer, agreed to stay until Alderson's successor was named.

January 17, 1956

September 1956

During the 30 years following Alderson's departure, memories of the integration nightmare faded, but never vanished. In the retrospective of time, longstanding questions can be answered and several observations are germane. The foremost question over the years: Could Alderson have avoided the years of agony that wracked the department? Yes, but with some equivocations. Alderson was a highly-principled person, albeit stubbornly unyielding. He believed in segregation and he fervently convinced himself that his legal obligations under the city charter prohibited assignments based upon race, albeit that some of the city's laws ran counter to the supreme law of the land. If Alderson is to be faulted, the criticism must stem from his failure to take definitive action when he realized integration was inevitable. He should have taken that action before the problem got beyond his control. Those who knew him best say that Alderson's charisma among members of the department and his leadership strengths were such that the firefighters would have accepted integration, however unhappily, if only he had acted sooner. It must be footnoted, however, that Alderson received precious little help or direction from most of the parade of Poulson-appointed fire commissioners during the integration years. Many of them were either segregationists themselves, or waffled on the subject. Many officers in Alderson's administration thought they were helping him but were, in fact, compounding his problems. Alderson received no help at all from the City Council. And he neither expected nor got any from Poulson, who publicly-postured integration, but privately-supported the segregation status quo. History demonstrates that valuable lessons can be learned from events of the past. With the integration horrors over, there were longstanding and positive fallouts...For starters, it helped propel one of the most outstanding black officers who ever served the department, Jim Stern, to become the LAFD's first battalion chief on February 6, 1968. Shern, thoroughly imbued with the LAFD's high standards of fire prevention and fire protection, went on to become chief of the Pasadena Fire Department and one of the few blacks ever elected president of the International Association of Fire Chiefs. Another upside of the integration aftermath, was that it reminded everyone of the fact that traditions die hard in the fire service. That the more than half-a-century of segregation tradition was broken in the relatively short period of time it was and without creating permanent rifts in the department, testifies to the resilience of the LAFD and its members. The hard and bitter lessons learned during the integration period surely had a helpful impact upon the entrance of women and other minorities into the uniformed ranks of the LAFD.

|

||||

|

||||