Bad

Night at Redondo Junction

By Loren B.

Joplin

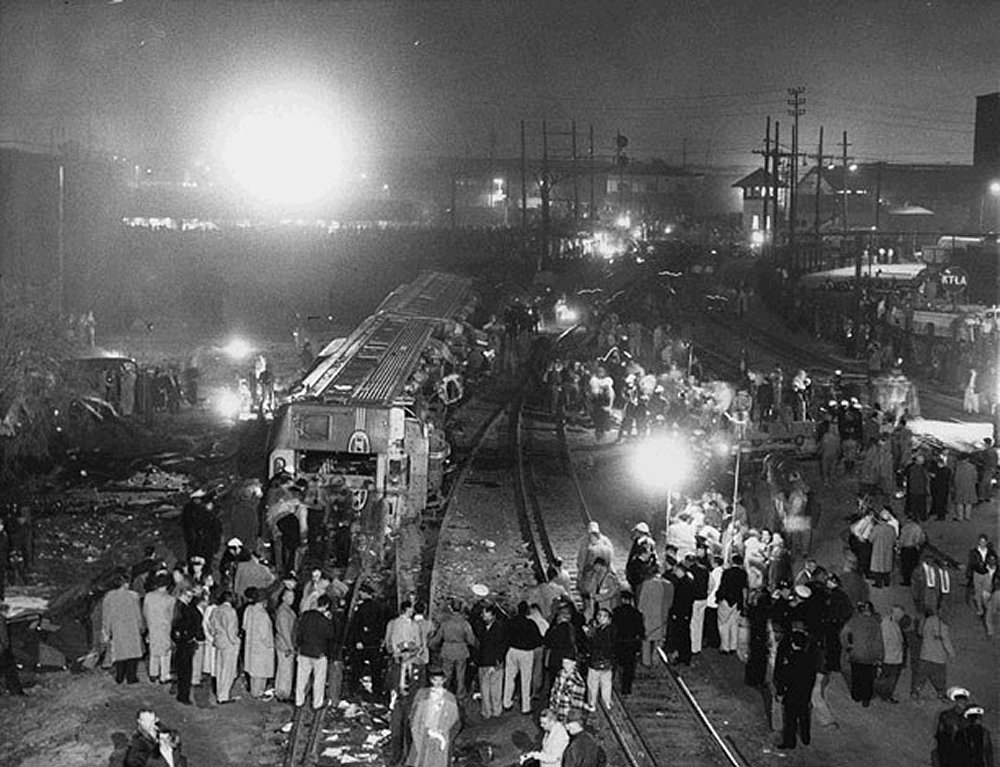

The

wreck of train No. 82 at Redondo Junction the evening of January

22, 1956, created quite a sensation in Los Angeles. Within

an hour of the wreck, KTLA Channel 11 was on the scene and

The

wreck of train No. 82 at Redondo Junction the evening of January

22, 1956, created quite a sensation in Los Angeles. Within

an hour of the wreck, KTLA Channel 11 was on the scene and

broadcasting live. Flood lights illumination the grisly

scene were donated by nearby movie studios. Note the silhouette

of the tower in the distance. -KTLA photo, Donald Duke

collection

Accidents happen in every field, and mistakes are a part of human nature. In transportation, the results can often be spectacular and tragic. That is what happened at Redondo Jct., California on the evening of January 22, 1956, when Santa Fe's RDC cars, filled with passengers headed for points on the Surf Line, overturned on the sharp curve near the tower killing 30 and injuring 117. Aside from newspaper accounts at the time, and brief mention in various books, not much has ever been written about the accident. I was on the staff of the Santa Fe General Manager in Los Angeles at the time, and one of my duties was to report all accidents and injuries to the proper government agencies and to the General Manager daily. Thus, I was involved at the outset in the tragic case. To

begin this story, the operation of the RDC cars must be explained.

Fred Gurly, president at that time, had approved the purchase of

two RDC cars in 1952. These cars were intended for

additional service on the San Diego line. Up to this time,

the line was running San Diegan streamliners, four times

in each direction, plus a local. These trains were well

patronized, especially on weekends, summer days and holidays,

but seemed to slack a little mid-week. At that time, there

was no commute business to speak of, and no Interstate 5 between

Los Angeles and San Diego. By placing the two RDC cars in

service, a total of 160 seats would be available. This was was

equivalent to three 52-seat chair cars of conventional

design. Of course, the RDC cars lacked the food and bar

service. It is my belief that as these cars were tried on

the Surf line, a study was being made to consider buying more

RDCs to replace conventional trains.

|

|

8 |

The Warbonnet |

The RDC cars proved to be very reliable, but there were no spares. If one went down or had to be held for maintenance, a conventional train had to be made up. On rare occasions, and during the week, a single RDC car would run when the other was down. The RDC cars were not without their problems, however. They were fast and ran like a streetcar, but had problems braking. Engineers complained about not being able to stop quickly and they had to be very careful to approach stations prepared to stop. There were times when inexperienced crews allowed the cars to completely pass stations they were supposed to stop at. Their quick acceleration surprised motorists at crossings as well, and they were involved in a lot of grade crossing accidents. So much so, that Santa Fe had the front of the cars plated with extra steel, painted them warbonner red and yellow, and added a mars light. During the 50s and 60s, grade crossing accidents were frequent and serious derailments did occur to all of Santa Fe's trains. This was one reason Santa Fe did not consider push-pull trains, and declined to order more RDC cars. Frank Parrish, the engineer on that fateful night, had not worked the RDC cars before, and was not familiar with them. He had been working the Grand Canyon between Los Angeles and Barstow when he decided to bid a run on the San Diegan, train Nos. 82 and 81. This assignment went to work in Los Angeles in the afternoon and operated train 82 to San Diego, laid over, and then returned in the morning on train 81 to Los Angeles. Frank made his first round trip to San Diego without incident and Sunday January 22, 1956, was his second trip. Frank had been a Los Angeles Division engineer for many years. He lived in San Bernardino and was 67 years old. He was a good employee with a good record. He had some minor incidents, but nothing that unusual. From the many men who worked with him that I knew, he had plenty of experience handling trains up and down the San Diego line. Many accidents happen when your life routine is interrupted by something out of the normal. When you drive to work the same way and the same route, you do it routinely without thinking. Change that routine and sometimes things go wrong. This may have played a part leading to the accident that night. Departing Union Station with a full train (engines and cars), train speed was normally quite slow until after leaving Mission Tower. Once leaving the interlocking, train speed would accelerate down the mainline which ran south along side of the Los Angeles River, past First Street Yard before braking to 15 MPH for the curves at Redondo Junction. Here the track curved to the right, or west, and then came back 90 degrees and headed east over the Los Angeles River. This normally took six minutes and if conditions were right, the train might reach 60 MPH. With the RDC cars however, acceleration was so quick that the time to travel this distance was only two minutes. A porter named Frenchy was on the train the night of January 22nd. He reported that the cars were filled to capacity and leaving Mission Tower, it was a fast ride as usual. Then, as the cars approached Redondo Junction, the train lurched and then the cars swayed twice before rolling over onto their left sides and sliding down the right-of-way. The tower man at Redondo Junction told of watching the RDC cars turn over on their left side and slide with a shower of sparks. When it all stopped, it was quite dark. In disbelief, he immediately called the authorities and railroad supervision. |

|

|

|

| Rescue

workers remove an injured passenger form one of the overturned

Budd cars. Thirty passengers lost their lives in the tragedy

and 117 sustained injures. -KTLA photo, Golden West Books collection |

|

When the accident occurred, employees from the adjacent Los Angeles Roundhouse ran to the scene to help in any way they could. Everything was shocking, horrible, and in a state of confusion. The two cars lay on their left sides. Baggage, debris, and people were everywhere. Quickly, railroad and emergency personnel began to arrive, followed by the media. Looters were reported taking possessions from the injured and dead. Many others were trying to help the injured. Frank Parish was seen crying in his wife's arms saying "he had disobeyed the rules". (His wife was riding on the train with him that night, and was not injured.) Road foreman of engines A.F. Murdock was on the scene, and immediately moved Mr. Parish to an office at the roundhouse to get him away from the many newspaper and television reporters that were starting to appear. R.D. Shelton, then General Manager, arrived quickly and questioned Frank about what had happened. Soon police detectives were there wanting to question Frank as well, but the railroad officials would not allow it, creating a heated moment. The railroad officials were worried about liability |

|

Second Quarter 2000 |

9 |

and the detectives were determined to ask questions. They finally allowed Frank to be questioned. Later, the District Attorney would make an investigating, but no charges were ever filed. As railroad officials tried to figure out just what had happened, emergency personnel probed the debris for the dead and wounded. Finally after many hours, the police cordoned off the area. After removing most of the injured, the railroad was asked to lift the cars up to remove more bodies, and find anyone that might have survived. Mr. Shelton quickly called for the big hook. There was no time to waste and Los Angeles only had one hook. So he called the Southern Pacific, which without hesitation, quickly sent their hook over with their crew. With the Santa Fe hook on one end and the SP hook on the other, the cars were slowly lifted back onto the tracks. Firemen and paramedics were able to complete the task of recovering all the bodies. The cars were re-railed and taken to the roundhouse, where they were headed into two stalls. Track damage was minimal and the line was soon reopened. A thorough investigation was made by the railroad and the various government agencies. Along with the District Attorney, all declared it was an accident by human error; failure to keep the speed of the train under control. Some had suggested that the time difference in train handling between the RDCs and a conventional train along the Los Angeles River caught the crew off guard, or perhaps they were daydreaming. Frank Parrish claimed he blacked out before the derailment. He quickly retired and the fireman was dismissed. "Nine Lives" Pat Shamblers, the rear brakeman, and "Frenchy" the porter were in the vestibule area and were able to prevent themselves from being thrown to the windows. Frenchy continued to work the San Diegans to his retirement. Pat was the luckiest trainman in the area, as he was in many of the major passenger derailments and accidents that happened on the Los Angeles Division. He was never seriously injured throughout his career, but almost died of ulcers in the 1960s. He did recover and retired as a conductor for the Santa Fe. A great deal of investigation was made as to why the fireman did not respond in time. There never did seem to be a good explanation as to why he did not react. In addition, the railroad officials tried to re-enact the incident at Redondo Junction, but since there were only two RDC cars, this was hard to do. The headlight was removed from the lead car and taken to the General Managers Office. The light was placed at one end of the hall and turned on to shine all the way down the hall to give some idea of the distance of light. The Santa Fe building was a block long in Los Angeles. A study was made of older engineers and their ability to control trains, but the older men all had the best safety records. The accident was a great black mark on the Santa Fe record. The year 1956 would go on to be a bad year for Santa Fe, when another employee would throw a switch in New Mexico in front of the Chief in May, and cause another serious accident. Mr. Birtja, the claim adjuster, told me that he settled all the cases concerning Redondo Jct. but one, spending $30 million. The RDC cars were held in Los Angeles for several months and then quietly moved because of the bad publicity, to Topeka for rebuilding. In mid-1957, the cars emerged from the Topeka Shops like new. DC 192, which was the leading car in the accident, was rebuilt with a baggage section. DC 191 was kept as it was delivered. These cars now ran between Newton and Dodge City. In this area, there were few crossings that had heavy traffic and the cars could now do local work. Later they were assigned to the El Paso -- Albuquerque run in 1965 and were retired in 1968. * |

|

| 10 | The Warbonnet |